I don’t have radiography equipment. The x-ray tube is heavy and doesn’t fit into my lightweight-low-cost-Ryanair-approved luggage plan I adopted for my art examination service. And it would be a lot of regulation issues to transport and operate an X-ray tube in a number of different countries.

Therefore, if the art to be examined could benefit from a radiograph I recommend to look for a local radiography facility. There are many in a big town; could be medical, security or industrial. It’s much cheaper and faster. Even if the operator has not experience with taking radiographs of works of art, in most of the case, the images would provide plenty of useful information.

This was the case for the Madonna and Child, at the Ingels Collection, Sweden. A radiograph was taken using an industrial X-ray machine. When it comes to paintings on canvas, often infrared transmitted (the lamp stay on the back of the painting) is pretty enough, but in the case of panel paintings, radiography is mandatory. I like to present in this post the radiography of the Ingels Madonna.

The Ingels Madonna is a relatively small panel painting (56,5 x 35,5 cm) on just one poplar board and by visual observation doesn’t show any other feature other than being one piece of sound wood. Though, radiography is often revealing about: pigments, craquelure and support.

Pigments

Since the wood is more than 3 cm thick, high energy X-rays are necessary and this implies that there is little contrast among pigments in the radiograph. On thick panel paintings only the very radiopaque pigments show up, the lead pigments (lead white, lead tin yellow, red lead) and vermilion (mercury). The other medium-radiopaque pigments (copper, iron) don’t leave any or very little contrast on the radiograph. Ultramarine, organic pigments, lakes are totally invisible.

On the Ingels Madonna only the thick ground appears in the radiograph, no paint is visible. Indeed, this is consistent with the period palette: red ochre, azurite, azurite and yellow lake for the green; all weakly radiopaque pigments. This palette is suggested also by the pigments’ appearance in the infrared image.

The flesh is IR transparent and not radiopaque. It means no lead white was used. Indeed, the paint is thin and translucent to allow the luminosity of the ground to suggest the flesh, as it’s typical of the Sienese school. Eventually, the radiograph shows some losses filled with radiopaque putty.

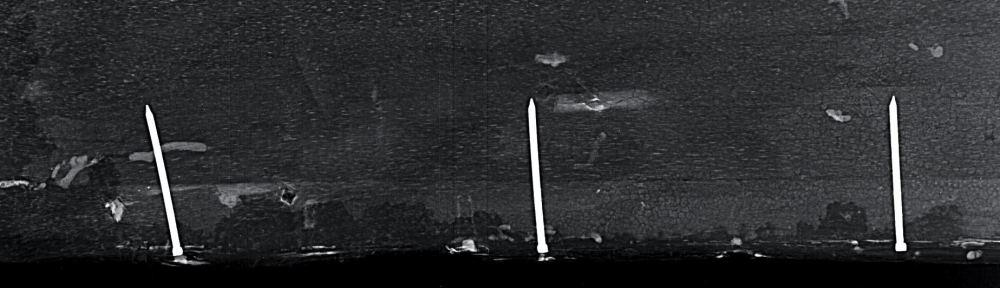

Madonna and Child, Ingels Collection, Sweden. Madonna and Child, Ingels Collection, Sweden. Visible (front and back flipped vertically), Infrared (IR) and radiography. Comparing Visible, Infrared and Radiography allows a preliminary pigments identification.

Craquelure

Panel paintings cracks go down to the ground and therefore they are visible in the radiograph. This property is used to distinguish real age cracks from craquelure that is only painted over (forgery) and doesn’t leave any trace in the radiograph.

Craquelure that goes down to the ground shows up in the radiograph while painted over cracks (fake) don’t.

Panel

The radiograph displays a crack of the right border of the panel fixed in place with three modern nails. Two metal fragments of presumably old and soft nails, with an arrow shape, are also evident on the left side, toward the center. The two main knots evident on the back show up on the radiograph.

Madonna and Child, Ingels Collection, Sweden. Radiograph with highlighted features.

References

Radiography for art: two must-have references, “X-Rays in Art”, focused on paintings, and “Radiography of Cultural Material” for anything else other than paintings.

Radiography is used extensively in art examination so there are plenty of radiographs scattered in many publications. For example, the National Gallery Bulletin is already a great source to learn how radiography is used to study a wide range of artists and periods. Following are some suggestions among literature specifically dedicated to radiography for art.

[1] A. Gilardoni, R. Ascani Orsini, S. Taccani “X-rays in Art” Gilardoni, 1977. Definitely the best reference to learn this subject matter applied to paintings. Gilardoni really knew what he was talking about. Gilardoni is a main company manufacturing x-ray machines. Most of the Italy’s airports x-ray scanners are Gilardoni’s. This book covers x-ray theory, method and applications for paintings. Of course it’s a bit outdated since it doesn’t cover new technologies such as digital radiography. Though, This’s not a big deal since you don’t really need to dwell with these technical details to correctly read a radiograph.

[2] J. Lang, A. Middleton “Radiography of Cultural Material” 2nd edition, Routledge, 2005. If you’re interested to cultural objects other than paintings this is the book for you. The section on paintings is very essential but the one on “paper” it’s informative.

[3] A. Burroughs “Art Criticism from a Laboratory” Greenwood Press, 1938. I actually didn’t read this book yet. I ordered it on Amazon more than 2 weeks ago but I fear it got lost. I read its review on the Burlington Magazine Volume 76, 443, 1940 and it seemed so interesting. I really like read those books wrote by pioneers of scientific art examination. Hope I’ll eventually find it in the mail.

[4] S. O’Connor, M.M. Brooks “X-Radiography of textiles, dress and related objects” Butterworth-Heinemann, 2007. As the title says, specifically covers radiography of textiles.

Thanks again to the Ingels family to let me use the Madonna and Child material.

Hello Antonino

This book could be useful to you “La técnica radiográfica en los metales históricos (Español e inglés)”

http://es.calameo.com/read/0000753359bd8dee5e9c4

I hope you you finally get your lost book 🙂

Carolina

Hi Carolina, thanks a lot for your link! very Interesting book and FREE! Yes, Just today I got that Burruogh’s book in the mail! Cheers!

On Wed, Mar 20, 2013 at 2:34 PM, Cultural Heritage Science Open Source