- Digital camera with high resolution and sensitivity to various light spectra.

- Light sources that can emit different wavelengths, such as ultraviolet (UV), infrared (IR), and visible light.

- Filters to isolate specific wavelengths.

- Software for processing and analyzing the images.

We begin this class with the analysis of palimpsests, focusing on technical photography methods. The first step is to introduce our photographic laboratory and show how the images are acquired. This is the first lesson on technical photography applied to reading palimpsests.

Our mock-up palimpsest contains two different layers of writing. The more recent text consists of medieval letters A and B, written with iron gall ink, which became widespread after the medieval period. Beneath this layer, we can barely see Greek letters—beta and gamma—written with carbon-based ink, which is typical of earlier, classical manuscripts.

Carbon-based ink and iron gall ink have different optical properties, and this allows us to use imaging techniques to separate them. In this lesson, we apply technical photography to distinguish the earlier classical text from the later medieval one. The experiment is carried out in our technical photography laboratory.

The camera is mounted overhead on the ceiling, with all cables routed above to keep the workspace clean and organized. On both sides, we have different light sources: UV lamps, halogen lamps that provide strong infrared emission, and dedicated IR lamps positioned above the object. This setup allows us to switch quickly between illumination modes.

For this experiment, we use the Technical Photography Kit, consisting of a modified digital camera and the Robertina filter set, including visible, ultraviolet, and infrared filters. Detailed instructions for each step are provided in the Technical Photography course.

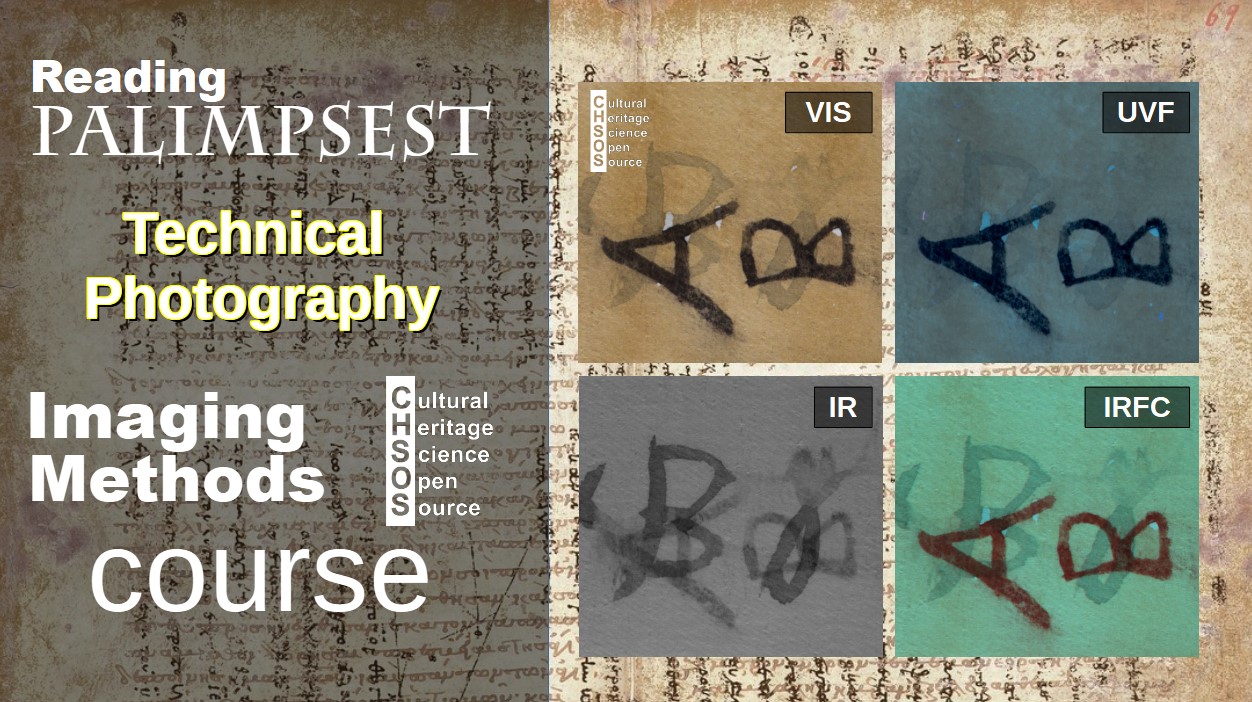

We now move to the computer to review the results. Technical photography is based on a standard commercial digital camera modified to record radiation from approximately 350 nm (UV) to 1100 nm (near infrared). By combining different lamps and filters, we obtain a set of technical photographs, each identified by a specific acronym and each providing distinct information.

We analyze the images in GIMP, an affordable open-source alternative to Photoshop. Each technical photograph appears as a separate layer. The visible image serves as a reference. The UV-induced fluorescence (UVF) image increases the contrast of iron gall ink, which absorbs UV radiation and does not fluoresce, making faded writing more readable. Carbon ink, by contrast, largely disappears.

In the infrared image, the Greek letters become much clearer, while traces of the medieval text remain visible. Infrared photography is particularly useful because it is fast and provides immediate feedback. Using a high-resolution commercial camera also ensures excellent spatial detail.

Finally, we generate an infrared false-color image, where iron gall ink appears red and carbon ink appears black. This method, demonstrated in detail in the Technical Photography course, allows a rapid visual separation of the two texts using minimal equipment: a camera, a few filters, and free software.

This concludes the lesson on technical photography for reading palimpsests. The key advantages of this approach are its low cost, speed, and simplicity. While it may not always achieve perfect separation, it is an excellent first step before moving on to more advanced methods.

In the next class, we will move to multispectral imaging using the Antonello system.

Learn Technical Photography for Art Examination

Technical Photography is one of the most powerful—and often overlooked—tools for the scientific examination of art and archaeology. If you are a conservator, scientist, or art collector and you are not yet familiar with this method, it is truly a missed opportunity. Using simple, affordable equipment and a clear methodology, Technical Photography allows you to reveal underdrawings, retouchings, material differences, and conservation issues in a completely non-invasive way. Far from being complex or inaccessible, it is an easy entry point into scientific analysis. In many cases, Technical Photography represents the first essential step toward a deeper understanding of artworks and archaeological objects.

Scientific Art Examination – Resources:

Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) – USA

The British Museum – Scientific Research Department – UK

Scientific Research Department – The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

C2RMF (Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France) – France

Rijksmuseum – Science Department – Netherlands